2021 report: AIA 2030 Commitment by the Numbers

Learn about the progress firms made in RY2021 toward the goal of carbon neutral buildings by 2030, including key takeaways on model energy usage, embodied carbon, renewable energy, building electrification, and post-occupancy evaluation.

AIA 2030 Commitment mission

Buildings are responsible for nearly 40% of greenhouse gas emissions globally. And we’re running out of time to mitigate this. To dramatically reduce emissions from the built environment, the AIA 2030 Commitment program empowers firms to track and measure progress toward net zero carbon with transparency and accountability.

Temperatures are already up 1.2°C from before the Industrial Revolution, and the world is currently on track to hit a 3.0°C increase, which is well above the 1.5°C threshold that the 2015 Paris Climate Agreement established. Giving ourselves an A for effort is not going to keep climate change in check; transformative climate action is critical. In 2021, for the second year in a row, signatories of the AIA 2030 Commitment reported their predicted energy use intensity data with an 80% reduction target. The program's target will go up to 90% in 2025 and to 100% full carbon neutrality, in 2030.

Since 2009, signatories of the 2030 Commitment have reported the predicted energy performance of all projects in their portfolio each year. The data, input via the Design Data Exchange (DDx), includes a project's baseline, its target, and its progress toward the target. Beyond these core metrics to track operational energy, the program expanded in 2020 to optionally track energy by fuel source, renewable energy, post-occupancy energy use, and embodied carbon.

Doubling its signatories these past five years and now representing over 56,000 AEC professionals, the AIA 2030 Commitment continues to be a part of leading the built environment profession in addressing the climate crisis. Reflecting 20,652 projects from 417 firms, this By the Numbers report for the 2021 reporting year measures how far we've come as a profession and shows how far we have to go.

Key takeaways

- 20,652 projects were submitted in the 2021 reporting period by 417 firms, an increase of 10% in firms reporting from the 2020 reporting period.

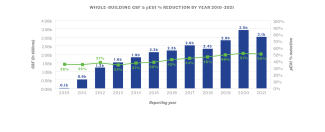

- 12,783 whole building projects totaling 3.1 billion gross square feet were reported in 2021 and achieved an average pEUI reduction of 50.3%.

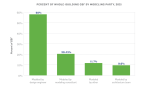

- 5.5% of whole building gross square footage reported in 2021 met the 80% target, an increase from 4.3% in 2020. This represents 161,625,553 gross square feet and 748 projects.

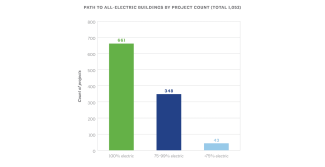

- In 2021, 2030 Commitment signatories reported 661 all-electric buildings, up 120% from 2020.

- 276 whole building projects were reported as net-zero in 2021, representing both 2.1% of projects and gross square footage. 67,399,844 gross square feet were reported as net-zero in total in 2021.

- 7,867 interior only projects reported in 2021 totaled 456,361,032 gross square feet, an increase of 24% reported from 2020.

- Interior only projects achieved an average 32.5% pLPD reduction, with a majority of interior only projects achieving the 25% pLPD target.

Introduction

In 2021, the COVID-19 pandemic continued to cast its pall over our day-to-day lives and the global economy.

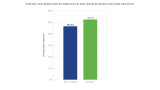

Despite obstacles, architects pushed forward with their clients, continuing to achieve higher-performing and lower-carbon designs. In 2021, the 20,652 projects reported achieved an overall 50.3% reduction in predicted energy use intensity (pEUI). The overall 50.3% pEUI reduction is slightly lower than the 51.3% reduction in 2020 but represents a strong overall trajectory, increasing from 35% in 2010.

The global supply chain has become unpredictable, and prices are volatile. Acquiring materials at the right time and the right price is vital to building industry success, and firms are finding this harder and harder to do.

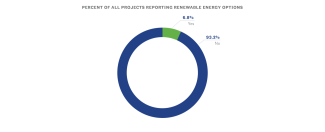

Inflation, a worldwide phenomenon facing the industry, has complex causes that include but aren't limited to the pandemic. Amid soaring costs, architects are learning to work within even tighter budgets, which can make certain sustainable design features, like photovoltaics, more challenging to use. Despite this, 6.8% of projects that 2030 Commitment signatories reported in 2021 including renewable energy, the majority generating energy through on-site solar photovoltaics.

Some sustainable design features, like robust envelopes that reduce peak loads and thus the size of the mechanical system, can ease first costs.

Although there were political setbacks in 2021, the Biden-Harris administration took strides to reduce building emissions and create more sustainable and resilient federal infrastructure.

Last year, a new 2021 rule required phaseout of hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs), which are highly potent greenhouse gases used as blowing agents for foam insulation and as refrigerants in mechanical systems. Additionally, President Biden signed an executive order requiring a carbon-neutral federal government by 2050. The order includes carbon-free electricity purchases by 2030, net zero carbon operations of buildings by 2045, and procurement of net zero carbon building materials by 2050. The administration has also launched the National Building Performance Standards Coalition, drawing upon the momentum of local and state governments to use design and building performance to address climate change.

Most notable has been the recent passing of the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022, the largest governmental climate investment. This includes incentives for clean energy, electric vehicle tax breaks, and pollution reduction measures. Altogether, the political landscape has continued to move forward with the pressing need for climate action, bringing forth the role of the built environment to reduce emissions and impact critical change.

In 2021, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) released the "code red" report.

"The alarm bells are deafening, and the evidence is irrefutable, " wrote UN Secretary-General António Guterres. “Greenhouse gas emissions from fossil fuel burning and deforestation are choking our planet and putting billions of people at immediate risk.”

Climate change is already devastating humanity with impacts that include more frequent and more extreme heat waves, flooding, droughts, and wildfires, according to a second IPCC report assessing global warming impacts and vulnerabilities.

But in a third report, the IPCC gave us hope, encouraging "concrete actions aligning sustainable development and climate mitigation" - something all architects can be a part of, including the more than 56,000 professionals employed at over 1,100 2030 Commitment signatory firms.

Net zero carbon has been the ambitious goal of the 2030 Commitment from day one, but it was framed exclusively in terms of operational energy until 2020. Over the past two years, the program has taken measures to help ensure we’re focusing not just on operational energy, but also more holistically on buildings’ life cycle of greenhouse gas emissions.

In 2021, 417 companies reported on 3.6 billion square feet across 106 countries via the DDx. These projects translate to an overall 50.3% predicted energy use intensity (pEUI) reduction for whole buildings and a 32.5% reduction in predicted lighting power density for interior-only projects.

Although pEUI remains the primary metric for whole buildings, the DDx now supports options to track embodied carbon and pEUI by fuel source. For projects reporting pEUI by fuel source, the DDx provides firms with insight into total estimated emissions intensity. By tracking these optional metrics, architects can start to expand their understanding of the carbon footprint, not just the energy performance, of the buildings they are designing.

Many universities and Fortune 500 companies have already made their own climate commitments and are asking for low- or no-carbon operations. This is happening in response to both climate risks and the increasing financial risks of investing in fossil energy, leading companies to the increasingly include climate-related risks in their financial disclosures. Their leadership has started a movement. Do we as a profession have the knowledge and resolve to deliver what the market is increasingly demanding?

We’ve heard success stories from firms that are consistently hitting the 2030 Commitment’s current 80% reduction target across their portfolios, as well as from those who are making meaningful improvements. Based on their achievements, we’ve identified five core strategies that can help you successfully push your firm and the industry toward zero carbon:

- Model building energy use at multiple design stages to keep the team focused throughout the process on passive design strategies and other energy-efficiency measures.

- Transition away from fossil fuels through building electrification.

- Use either on-site and/or off-site renewable energy.

- Reduce the embodied carbon of buildings to help mitigate the upfront emissions caused by the manufacture of building materials.

- Measure energy performance post-occupancy to verify assumptions and learn lessons for next time.

If your firm hasn't already signed onto the 2030 Commitment, learn more about joining fellow 1,100+ signatories here. Let’s take a deeper look at these core strategies and how 2030 Commitment signatories are successfully adopting them.

Key takeaways

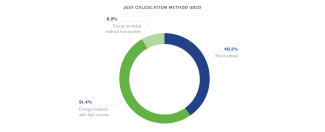

- 7,631 projects reported in 2021 were energy modeled, including 1,056 by fuel sources.

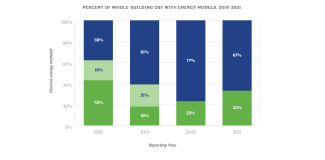

- 59.7% of whole building projects reported in 2021 by count included at least one energy model.

- 2 billion gross square feet were energy modeled in 2021, representing 66.6% of the gross square footage reported by whole buildings.

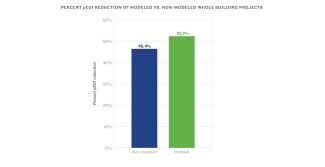

- Whole building projects reported with an energy model in 2021 achieved an average pEUI reduction of 52.3% while whole building projects reported without a model achieved an average pEUI reduction of 46.4%.

Model building energy use at multiple design stages

Measuring predicted energy use intensity (pEUI) in buildings is a vital step in designing high-performance buildings, but it’s not a one-and-done procedure.

In fact, the best way to get the full value of energy modeling is to start very early with a baseline and target pEUI, as well as a “simple box” or “shoebox” model, to compare options and help optimize orientation and massing. Comparing options should continue as the design progresses.

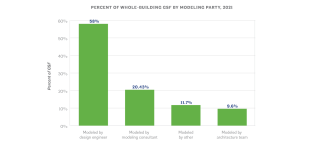

Architects can use early energy modeling tools themselves, or they can work closely with modeling professionals. Either way, architects need to take the lead on energy modeling, driving the process and ensuring that design changes made by everyone on the team respond to the models’ findings. For projects reported with energy models in 2021, 18.8% were modeled by a member of the architecture team, 51.7% by a design engineer, 20.6% by an energy modeling consultant, and 7.7% by other parties.

Too often, energy modeling is done after design is over just to prove code compliance or to achieve a building certification credit. This misses all the opportunities to compare features to inform daylighting, develop building envelope specifications, and implement other passive design strategies.

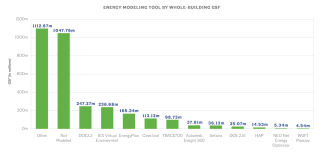

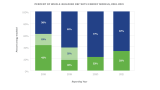

Modeling is the only way firms can reliably estimate how their projects will perform so they can make changes before the project is built, and it allows firms to help their clients predict and reduce future utility costs. Together with cost estimating, it’s also the best way to identify the most cost-effective ways of achieving high performance—thus using clients’ money responsibly to arrive at the right solutions. In 2021, more than 7,600 whole building projects reported at least one energy model, equivalent to 66.6% of gross square footage reported. Most projects’ energy models were conducted in the construction administration phase.

In the past, modeled projects in the DDx have consistently had greater pEUI reductions than non-modeled projects. This occurred in 2021, with modeled projects demonstrating a 6% greater reduction of pEUI than non-modeled projects.

And for projects pursuing net zero energy—276 for this reporting year, and that number should skyrocket as we approach 2030—modeling is an imperative part of the process, allowing the project team to predict how much renewable energy will be needed.

100% modeled: BRIBURN

The founders of BRIBURN made a commitment in 2013 to develop an energy model for every building project on the boards. They haven’t looked back.

Harry Hepburn, AIA, principal at the firm, says modeling serves many purposes—not just reducing pEUI, though of course that’s the biggie. For example, using WUFI Pro software, the firm can perform both energy and hygrothermal modeling to help manage moisture. This came in handy for the Maine Coast Waldorf School’s high school building when it became evident the building was close to having moisture issues.

Using a combination of energy and hygrothermal modeling, the team was able to analyze unvented roof conditions as well as foundation wall conditions and then adjust accordingly to ensure the risk of condensation or mold growth was substantially low. In addition, a Larsen truss wall assembly was used on the north face of the building where a standard 2-foot by 8-foot wall with rigid insulation would not dry as quickly. The Larson truss assembly preserves energy performance while allowing the exterior to dry.

For a private residential project of BRIBURN's, the owner was interested in the benefits of triple glazing and tuned solar heat gain coefficient (SHGC) and what that meant for energy reduction and cost savings. “What we ended up doing was looking at both double- and triple-glazed window performance, and we added in SHGC to understand the impact of the different glazing and what it meant for energy use and then cost,” Hepburn said. Based on the energy model, low SHGC would be ideal for the west side of the house, but there was a cost premium. By using energy modeling, the team was able to determine that the energy savings over time would make it worth the extra upfront dollars.

Overall, according to Hepburn, the energy model helps educate clients about energy efficiency and its value. While a client may not understand the difference between two wall types, he said, “When you share the numbers and you convert that to a dollar amount in terms of savings, it becomes a very useful tool.”

- Explore the Architect’s Guide to Building Performance to learn about common approaches to building simulation and answers to frequently asked questions.

- The AIA+2030 Online Certificate Program is a robust course series that traverses topics ranging from passive systems and load reduction to high performing building systems and renewable energy.

- Consult the ROI of High Performance Design to get equipped with talking points on the value of sustainable design and to convey the value you bring as a sustainability leader.

- Hear from three firms on how they’ve achieved Energy Modeling and High-Performance Design from this course at AIA-ACSA's Intersections Conference.

Key takeaways

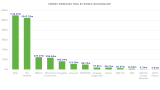

- 661 all-electric projects were reported in 2021, an increase of 120% from 2020.

- All-electric projects reported in 2021 totaled 76,729,668 gross square feet.

- 1,056 projects were reported with energy modeled by fuel sources in reporting year 2021, an increase of 57.8% from 2020. This represents 8.2% of all whole buildings reported in 2021 and 13.8% of whole buildings that were energy modeled.

- 167,008,729 gross square feet were reported with energy modeling by fuel sources in 2021, representing 5.3% of all whole building gross square footage reported and an increase of 80% from 2020.

Move beyond fossil fuels through building electrification

The 2030 Commitment originally focused exclusively on energy performance without regard for where the energy came from. But it’s become increasingly clear that, although we may reach net zero energy while still using fossil fuels in our buildings, we will not reach net zero carbon.

That’s why in 2020 the DDx began offering the option to report energy models by fuel source, meaning users can indicate how much energy comes from fossil fuels and how much from electricity. In 2021, the number of projects reporting pEUI by fuel source increased 57.8%, totaling 1,056 projects. This represents 167 million total gross square feet, an 80% increase from 2020.

The option to report energy modeling by fuel source is helping project teams blaze a trail toward universal building electrification—a wholesale switch from fossil-fuel-powered equipment to electricity-powered equipment. In 2021, 2030 Commitment signatories reported 505 all-electric buildings, up 67% from 2020.

Why electrify? In many regions, it’s already the case that all-electric buildings have lower carbon emissions than those using fossil fuels. And with the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act in place, the U.S. is investing $20 billion in grid upgrades that include greater resilience and cleaner energy. So, preparing for electrified infrastructure now means lower carbon emissions in the future.

Leveraging a clean grid: Mahlum

Mahlum, with offices in Portland, Oregon, and Seattle, Washington, first signed onto the 2030 Commitment in 2009. It now has a firm-wide goal of zero embodied and operational carbon for all its projects. Building electrification is becoming a bigger and bigger part of that, said Jesse Walton, AIA, Associate Principal at the firm.

“It’s a combination of our internal values around pushing for low-carbon design and our clients’ values,” Walton explained. “Our grid is so clean out here in the Pacific Northwest. It makes a lot of sense if you’re pushing for low carbon to go to all electric.”

In 2021, Mahlum submitted all its projects by fuel sources for the first time. This year, 28% of submitted projects were all electric, and the firm hopes to improve on that benchmark as time goes on.

Walton emphasized that 2030 Commitment signatories shouldn’t get discouraged when trying something new. “Our data’s not perfect,” he conceded. Many of the projects didn’t even have fuel-source data, so the team used a 50-50 gas-electric split as an estimate. Just like with pEUI, “the first couple years, it’s a bit chaotic,” he said. “Then you begin to understand how to better collect, check, and analyze that data.”

Walton also noted that electrification often means using heat pumps, which require refrigerants that can have a high global warming potential (GWP). “I think the electrification and carbon question is a complicated one,” he said. A recent net zero energy project “has an air-source heat pump system that contains refrigerants. If the goal is net zero carbon, we should not exclude refrigerants in our carbon calculations just because we’re uncertain of the math.”

With that said, regulatory agencies are stepping up around the world—including in the U.S.—to phase out the refrigerants with the highest GWP, and electrification remains a necessary transition to a fossil fuel–free future.

- Browse through the Framework for Design Excellence’s Design for Energy principle to glean why designing for all-electric buildings is a priority strategy to decarbonize.

- Read AIA’s Climate Action Plan to understand why all-electric buildings and increasing electrification is key to reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

Key takeaways

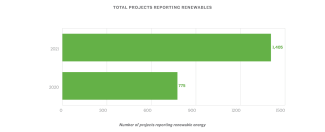

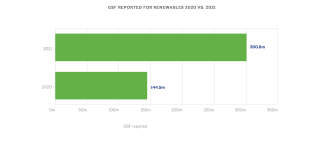

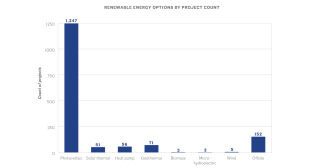

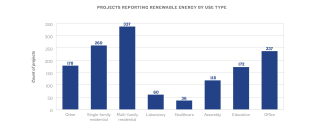

- 1,405 projects were reported with renewable energy in reporting year 2021, an increase of 81.3% above 2020. In total, 6.8% of projects reported in 2021 included at least one kind of renewable energy.

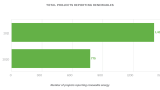

- Gross square footage reported in 2021 increased 108.1% from 2020, totaling 300,792,682 gross square feet. 8.3% of all gross square footage reported in 2021 included renewable energy.

- 95% of projects that reported renewable energy in 2021 used on-site renewable energy and almost 89% used on-site solar photovoltaics.

- 77.5% of the 292 net-zero projects reported in 2021 used at least one kind of on-site renewable energy and 6.8% used two or more kinds of on-site renewable energy.

- 51 of the 292 net-zero projects reported in 2021, or 17.4%, used off-site renewable energy.

- 9.9% of the 292 net-zero projects reported in 2021, 29 projects total, used both on and off-site renewable energy.

Use either on-site or off-site renewable energy

As the pEUI target of the 2030 Commitment has ramped up, the need to add renewable energy to projects has crystallized. Once projects have reduced predicted energy use intensity (pEUI) as much as possible, renewables are necessary to reach net zero or net positive terrain. And we’ll need more and more renewables as 2030, with its net zero target, approaches.

Additionally, buildings that have renewable energy paired with electric or thermal energy storage can actually help clean up the grid. That’s because they can reduce grid stress during peak times, preventing the need for utility companies to power up dirty “peaker plants.”

Even if a building owner isn’t interested in, or can’t afford, renewables right away, it’s vital to ensure they can be added later. A “renewable-ready” building has design elements that make it easy to add renewables after construction. For example, optimizing building orientation, roof design, and electrical systems can ease the cost of adding solar photovoltaics (PV) and can improve PV performance in the future.

Fortunately, there are multiple ways to add and pay for renewable energy.

- On-site options include solar photovoltaic, solar thermal, wind turbine, heat pump, geothermal, micro-hydroelectric, and biomass.

- Off-site options include virtual power purchase agreements, direct ownership of an off-site system, purchase of unbundled renewable energy certificates (RECs), joining a long-term community renewable program, renewable energy investment fund, direct access to wholesale markets, and green retail tariffs. But buyer, beware! It’s important to verify additionality, meaning that the building owner is purchasing renewable power that would not have existed otherwise.

PV isn’t the only game in town, and the DDx also allows users to report on wind, micro-hydro, and several other renewable energy sources. Yet, today, solar remains the most commonly reported type of renewable energy, with on-site solar PV representing 88.7% of the projects reporting renewable energy in 2021.

In 2021, 1,405 projects totaling 300 million square feet reported using renewable energy, an 81.2% increase in the number of projects and 108.1% increase in gross square footage. Of these, 1,335 projects used on-site renewables, 143 projects used off-site renewables, and 87 used both.

Sustainability for everyone: Overland Partners

“We didn’t know exactly how we were going to get there, but there was a values alignment,” said John Byrd, AIA, of Overland Partners’ decision to sign on to the 2030 Commitment in 2014. As director of design performance at the firm, Byrd takes the 2030 Commitment very seriously.

“The first couple years were very influential,” Byrd noted. “It forced us to adopt energy modeling across the office; this challenged our intuitions and made us better designers and architects all around.”

But as the thresholds went up over time, “we realized that efficiency alone wasn’t going to get us there: we were going to need renewables in as many projects as possible.” Since that realization, the firm has pushed for net zero and net positive performance on a large number of projects.

Sometimes that has meant convincing clients whose values may not fully align with the 2030 Commitment.

On one residential project, the client expressed skepticism about climate change. “This was not the obvious client for pitching solar or any other traditional sustainability criteria,” said Byrd. “But if we believe it’s for everybody, it needs truly to be for everybody.” Thus, the conversation focused on things the client cared about—energy independence and return on investment. “We were able to make it one of the most sustainable private residences we’ve ever designed,” Byrd noted.

“With regard to sustainability, we truly believe there’s something for everyone,” Byrd added. “The earlier on you start, the better. Make it integral to what your clients are trying to accomplish."

- Explore the Architect’s Primer on Renewable Energy for a starter guide on how to leverage on-site and off-site renewable energy in your projects.

- Learn how to employ renewable energy at the project and portfolio-scale in Course 8 of the AIA+2030 Online Certificate Program focused on the role of renewable energy.

- Browse through the Framework for Design Excellence’s Design for Energy principle to understand how projects can integrate renewable energy and why renewable-ready design can be pursued for future on-site renewables.

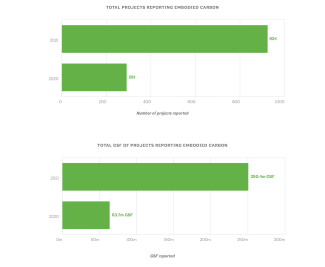

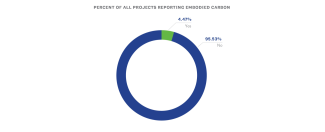

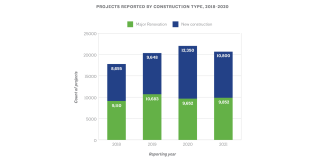

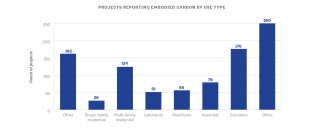

Key takeaways

- 83 firms reported 924 projects with embodied carbon in reporting year 2021, up from 55 firms and 292 projects in 2020. This represents 4.4% of all projects reported in 2021 up from 1% in 2020.

- Projects totaling 250,439,074 gross square feet reported embodied carbon in 2021, an increase of 293.1% from 2020. In 2021, gross square footage with embodied carbon represented 6.9% of all gross square footage reported.

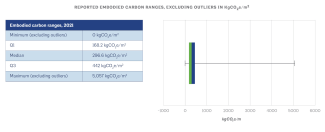

- For new construction projects reported in 2021, the median embodied carbon was 324.2 kgCO²e and for existing buildings the median was 106.8 kgCO²e.

- 59.6% of projects reporting embodied carbon were new construction projects and 40.3% were major renovations of existing buildings in reporting year 2021.

- 92.7% of projects reporting embodied carbon in reporting year 2021 were whole building projects and 7.2% were interior only projects.

- 123 projects that reported embodied carbon, or 13.3% of the reporting year 2021 total, included biogenic carbon in their calculations.

- A total of 924, or 4.47%, of projects included embodied carbon data in 2021, more than triple the number of projects reporting embodied carbon data in 2020.

Improve the embodied carbon of buildings

It’s clear that we need to reduce the amount of carbon our buildings emit over time through energy use—their operational carbon. But improving embodied carbon—the emissions associated with building materials —is perhaps even more urgent.

That’s because most of those emissions happen before the lights even go on, meaning we’re releasing massive quantities of greenhouse gases into the atmosphere just by constructing a new building. Production of concrete and steel alone accounts for 11% of global carbon emissions.

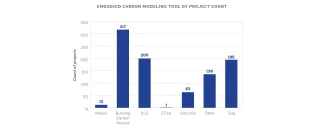

With growing awareness about embodied carbon, the DDx was expanded in 2020 to allow users to track it. A total of 924, or 4.47%, of projects included embodied carbon data in 2021, more than triple the number of projects reporting embodied carbon data in 2020. Embodied carbon data was reported by 83 firms in 2021, an increase of 50.9% from 2020, and represented more than 250 million gross square feet.

How can we reduce embodied carbon? The best answer is to reuse existing buildings and materials. When new construction is unavoidable, teams can use whole-building life-cycle assessment. This type of modeling allows for the comparison of different materials and systems in order to optimize for performance and carbon.

Although your embodied carbon results don’t contribute to pEUI reduction targets, AIA encourages tracking them as part of your climate action goals. By measuring and tracking embodied carbon, you can contribute to profession-wide embodied carbon literacy and accountability.

Stop building: WRNS Studio

Embodied carbon isn’t the first thing clients talk about, said Pauline Souza, FAIA, partner at WRNS Studio—and that’s why architects should be bringing it up. WRNS has started using the Tally whole-building life cycle assessment tool to model embodied carbon on all types of projects, whether clients ask for it or not.

“We have this new, better understanding that right now matters more than 50 years from now,” Souza said. “Remember when 2050 and 2030 were way out there? Now they’re a few blocks away.”

The firm has taken a “swat team” approach to proliferating the practice, with a few people learning Tally and then teaching it to a few more people and so on.

By integrating lifecycle assessment into their process, Souza said, the firm has learned that building reuse is by far the best way to reduce upfront emissions.

At the Microsoft Silicon Valley Campus, the firm reused 240,000 square feet of space and added 400,000. The new construction was done with a hybrid of mass timber and steel. “We thought the mass timber was going to be a huge number,” Souza said, in part because of carbon storage and in part because it served as both structure and finish. But that made a minimal difference compared with saving an existing lab space.

“How do we stop building?” asks Souza. “What do we need to know in order to move our clients toward buildings that exist?”

In the meantime, using whole-building life cycle assessment is key to learning more about embodied carbon impacts and where they come from, Souza argued. “Every project has materials, so every project can track its embodied carbon.”

- AIA-CLF's Embodied Carbon Toolkit for Architects provides a 360 view into embodied carbon in the built environment, why it matters, and strategies to reduce it.

- Could you use talking points with clients for the return on investment for embodied carbon? Check out AIA’s ROI: Designing for reduced embodied carbon for pointers on design, material selection, renovation, and future proofing. Take your knowledge of embodied carbon to the next level with AIA’s 12 course Embodied Carbon 101 series that dives into nuances ranging from envelope and structure to carbon accounting and certifications.

- Explore high impact strategies, resources, and case studies in the Framework for Design Excellence’s Design for Resources principle, which includes embodied carbon and other complementary material considerations.

- Read AIA Renovate, Retrofit, and Reuse to learn about six guiding principles that can be applied to any existing building project to unlock the many benefits of leveraging our current building stock, embodied carbon included.

Post-occupancy evaluation

Collect building performance data during occupancy

Predicted EUI is the primary metric used for tracking success in the DDx. But energy models can be imprecise tools, and once a building is in use, its performance may differ from the expectations for a variety of reasons. This often happens because of longer occupancy hours than the model assumed, but the need for mechanical system tuning is also a common culprit.

Post-occupancy evaluation (POE) allows architects to access performance data and, ideally, to assess and address any problems. When POE reveals that a project is consuming more energy than expected, these lessons learned can be invaluable for future projects.

Unfortunately, POE is rare. Often, it’s seen as an extra service requiring extra fees, and owners aren’t keen to commit to it if the topic comes up too late in the process. Sharing data regularly is also one more thing for busy facilities professionals to attend to.

But things are starting to change as more and more owners pursue higher-performing buildings and net zero energy. Programs like the International Living Future Institute’s Zero Energy Certification and the U.S. Green Building Council’s LEED Zero require actual energy data to verify achievement. Architects need to lead the growing movement toward performance verification—which has the added benefit of helping architects understand whether their designs are working as intended.

To support that goal, the DDx offers the option of tracking projects’ actual energy performance over time. Once a project is completed, firms can enter the energy use intensity from an overall utilities bill or by fuel source, which is especially helpful in assessing how on-site renewables perform in practice. But post-occupancy energy data remains a new frontier in most 2030 Commitment signatories’ reporting practices. So far, 329 projects, including 92 projects in 2021, have reported post-occupancy data in the DDx.

A culture of care: KieranTimberlake

Why don’t more projects have solid post-occupancy performance data? It’s not a technical challenge but rather a cultural one, argues Kit Elsworth, Associate and building performance specialist at KieranTimberlake.

“It’s not about sensors; it’s not about the actual methods of data collection,” said Elsworth. “It’s about creating a culture of care, educating ourselves, and dedicating resources to share knowledge from our projects.”

It’s also a problem that post-occupancy evaluation is seen as an add-on service that too often doesn’t come up until the project is complete. Instead, teams should be looking for opportunities to bring up data collection early so that it’s part of the project from day one.

That way, the right technology can be in place, and the right people can be involved.

Look for opportunities to align with clients’ own values and commitments, advised Elsworth. For example, in KieranTimberlake’s work with the University of Washington–Seattle, the team discovered that the university has a campus-wide commitment to incorporate living labs into all future building projects. “We harnessed that commitment to identify opportunities to integrate metering into the building that would not only support the university’s goals, but also facilitate POE,” said Elsworth. “By establishing this goal early, post-occupancy evaluation is a part of the design and not seen as an added cost.”

Elsworth pointed out that building owners are facing increasing regulatory pressure around measured energy performance, with laws like New York City’s Climate Mobilization Act, Washington, D.C.’s Building Energy Performance Standards, and Colorado’s Energy Performance for Buildings Act proliferating around the country.

“The writing is on the wall. We’re seeing a lot of attention and momentum around actual building performance, and architects are in the best position to be driving the conversation,” Elsworth said. “Start now so you can best position your projects and firms for meaningful building data collection.”

- Browse through best practices, case studies, and the highest impact strategies to apply lessons learned from past projects in the Framework for Design Excellence’s Design for Discovery principle.

- Learn how post-occupancy evaluation can improve your practice in Emerge by AIAU: The Building is Never Done, Improving Your Practice Using Post Occupancy Evaluation.

- BuildingGreen Articles on Post-Occupancy Evaluations look at social science research as well as more anecdotal case studies, and we share what actually works and why.

- Whole Building Design Guide on Post Occupancy Evaluations (POE) shares that every lesson learned turns the curve towards more successful buildings.

- RIBA highlights leading Post-Occupancy Evaluation (POE) guidance including a primer, report, and pathways to knowledge.

- Explore AIA California’s webinar on Post-Occupancy Evaluations + Building Performance Data Gathering as part of their Climate Action Series.

The AIA 2030 Commitment program offers architects a way to publicly show their dedication and track progress toward a carbon-neutral future.

Access AIA’s yearly 2030 Commitment By the Numbers reports starting in 2010.